Asset-building. Dal risparmio (integrato) alla laurea: come sostenere l'istruzione terziaria dei ragazzi e delle ragazze a basso reddito

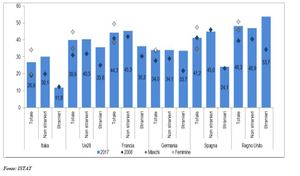

L'Italia è povera di laureati. Nel 2017, secondo le stime ISTAT, solo il 18,7% degli italiani tra i 25 e i 64 anni aveva concluso con successo l'università, contro una media europea del 31,4%. Il distacco risulta particolarmente pesante nella fascia d'età 30-34: tra i giovani ha una laurea soltanto il 26,9%, mentrel'Unione, col 39,9%, viaggia a ben altra velocità.

L'obiettivo nazionale che il nostro paese si era dato per il 2020 - 26 laureati ogni cento 30-34enni - è stato raggiunto e addirittura superato, ma siamo ancora molto lontani dal traguardo del 40% previsto dalla strategia Europa 2020. La distanza diventa abissale guardando ai paesi in cima alla classifica Ue (l'Italia è penultima, dopo la Romania): 58,7% di laureati in Lituania, secondo Eurostat, nel 2016; 54,6% in Lussemburgo; 53,4% a Cipro e poco meno in Irlanda.

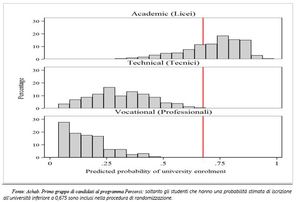

Questa mancanza di opportunità educative genera disuguaglianze a lungo termine nella vita dei giovani italiani, ma per le famiglie a basso reddito è ancora difficile affrontare il costo dell'istruzione terziaria. Come e dove si può intervenire? Tra le forme di sostegno economico che possono facilitare l'accesso all'università si sta rivelando particolarmente efficace l'asset-building. Ma cos'è e come funziona il "risparmio integrato"? Un'esperienza importante: Percorsi.

Testing a Social Innovation in Financial Aid for Low-Income Students: Experimental Evidence from Italy

Italy has few graduate students. In 2017, according to ISTAT estimates, only 18.7% of Italians aged 25-64 had successfully concluded university, as against a European average of 31.4%. The gap is even wider in the 30-34 year-old population: as little as 26.9% have a degree, with respect to an EU average of 39.9%.

The national target of 26% in the 30-34 age bracket by the year 2020 was achieved, but Italy is well behind the 40% target set by the Europe 2020 Strategy. The gap becomes a chasm if we look at top ranking EU countries (Italy being last but one, before Romania): in 2016, according to Eurostat, Lithuania had 58.7% of graduates, Luxembourg 54.6%, Cyprus 53.4% and Ireland following closely.

This lack of educational opportunities engenders long-term inequalities in the lives of young Italians, but low-income families still find it hard to bear the cost of university education for their children. What is to be done, and how? Asset-building programmes are proving effective to support access to university. But how do topped-up savings actually work? An important experience: Percorsi.

Focus

Focus